MOUNT KANCHENJUNGA AS ELDEST BROTHER AND PROTECTOR OF SIKKIM DARJEELING HIMALAYA

Charisma K. Lepcha

Rong religion has been of interest to colonial administrators, ethnographers, and anthropologists ever since they set foot in the Sikkim and Darjeeling Himalaya. Upon arrival in these borderlands, they were surprised to find a group of people who did not practice either Buddhism or Hinduism–the world religions with which they were familiar. The religion of the Indigenous people was seen to be confusing, “contradictory,”1 “double-layered,”2 “atheistic,”3 and there was “nothing spiritual”4 about it. Most of these scholars were not able to understand or fathom the religious moorings of the community of people who traced a mountain as their place of origin and shared kin relations with the stones and the trees.

The Rongs are the Indigenous people of Sikkim and Darjeeling Himalaya who believe their creator God, Itbudebu Rum, made the first man and woman from the snow of Mt. Kanchenjunga (Kongchen Konghlo), their sacred place of origin. The Rong country is called Mayel Lyang, which today stretches across Sikkim, Darjeeling, and Kalimpong in India, southwest Bhutan, and eastern Nepal. They call themselves Rong from Rongkup/Rumkup, which means “children of snowy peak”/“children of God,” identifying themselves as the offspring of both nature and God. The popularly used Lepcha nomenclature to identify the community is an exonym with derogatory connotations; hence, the original term “Rong” will be used in this article.

The Rong religion is called Mun-Bongthing, also known as Munism and Bongthingism, deriving its name from the female and male ritual specialists who act as mediators between gods, humans, and spirits. They are seen as powerful shamans and are required to officiate the different rites of passage. Early anthropologists mention “munism” or the “mun religion” in their writings, distinguishing the Indigenous religion from Buddhism, reflecting how our idea of religion is most often shaped by the contemporary understanding of world religions. The colonial conception of religion, therefore, did not fit the Rong belief system since, like other Indigenous people around the world, they did not have a word for “religion” per se. The closest description of their religion from one of the early colonial texts suggests that “though outwardly professing Buddhism, they are at heart confirmed animists, worshipping the spirits of mountain, forest, and river.’”5Rong cosmology is in fact filled with “reverence for nature, ancestral spirits, and sacred landscapes.”6 Interestingly, both Buddhism and Christianity had already seeped into Rong society by the time Rong people began to be studied. The Buddhist missionaries from Tibet and the Christian missionaries from Scotland7 had already introduced Buddhism and Christianity as the acceptance of these two religions led to the creation of Buddhist Lepcha and Christian Lepcha identities fracturing the community along religious lines. Rong religious scholarship then flourished by examining the influence of these world religions on traditional lifeways, though it was limited to religious identity and social cultural change.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in Rong religion and its relation to the environment. Such studies are a departure from earlier religious perspectives and make an attempt to understand the Indigenous religion in its own terms. The consciousness perhaps began in 2007, when Rong activists protested against hydropower projects8 in their “ancestral land”/“holy land.” Of the twenty-six dams to be constructed in Sikkim, six were proposed inside Dzongu—the protective “reserve” set aside for the Indigenous Rongs since the time of the King.9 The royal notification in 1958 forbade “outsiders” from entry and residence in the culturally homogenous Rong reserve. Because of its special status, Dzongu has often been the homeland for Rongs around the world. With the emergence of dams, their existence felt threatened as they began articulating the religio-cultural connections to the land drawn from a rich history and lifeways embedded in the landscape. Dzongu was indeed the last bastion of Rong culture and was seen as a “living entity.”10 It is believed that the creator sent the first couple, Fudongthing and Nazongnyoo, to live in Dzongu, and it is known as fokram takram–meaning the source of Rong origin and life. In that, Dzongu holds a past, present, and future, with a “consciousness and a will toward life”11 and the dam activists defended their sacred geography. “We want our sacred, holy, ancestral land, Dzongu, where the souls of our ancestors rest to be left alone” read one of the flyers during a hunger strike in 2007.

At that time, nobody paid heed to their words and their struggle. After all, they were just a handful of Rong youth from the reserve area who probably did not know what they were doing, as the state labelled them “anti-Sikkimese.” Sikkim is the second smallest state in India with a population of only six hundred thousand, and protests against dams by a micro-minority community was negligible. But the youth persisted. Their indefinite hunger strike went on for over nine hundred days as four out of six projects were scrapped, and they became the voice of conscious resistance. Though their cries were related to the sacredness of the landscape and the defense of their ancestral memories, the uphill battle had given birth to Indigenous environmentalism in a rather unexpected manner. During the early days of protests, people were surprised that the Rong activists chose to highlight the religio-cultural reasons to oppose hydroelectric projects. It seemed distant from the environmental focus most dam activists across India were advocating. Little did people understand that the environmental wisdom was embedded in their cultural lifeways, as the interaction with “biodiversity and local bioregions” was integrated into everyday life.”12 In that, the transformation of Dzongu from “homeland” to “holy land” was living proof that religion and ecology had reclaimed the Rong worldview for the entire community.

Rong religion has mostly been studied under the shadow of Buddhism, and the landscape is often viewed from the Buddhist perspective. For instance, Mt. Kanchenjunga, the origin mountain for Rong people, has been appropriated by Buddhism and made into the guardian deity, as Kanchenjunga is revered as the guardian deity of Sikkim even today. For the Rong people, Kanchenjunga reflects their sacred origin—a history that took place in a fabled primordial time of the “beginnings.”13 It is believed that when the Himalayas were created, Kanchenjunga was the first creation and is revered as the eldest brother–Anum Timbu. The acknowledgement of Kanchenjunga as Anum Timbu tells us of the human and nonhuman kin relations with the mountain. There is a reciprocal relationship in which the eldest brother protects the younger siblings as they bestow respect on him.

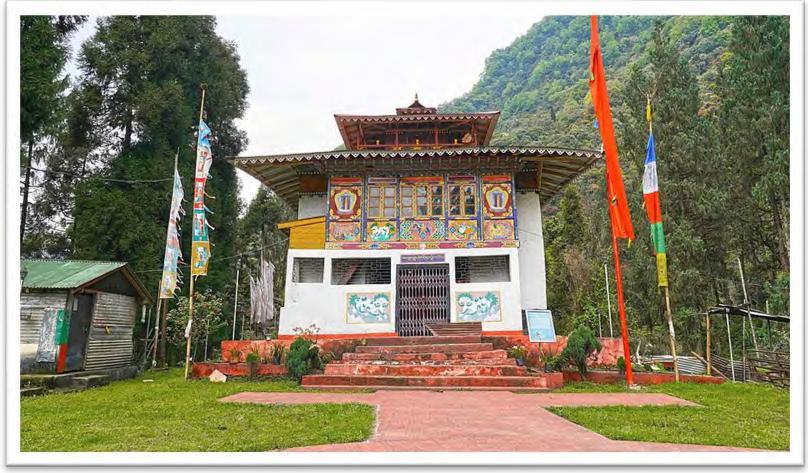

Reverence for Kanchenjunga is also evident in the evocation of the mountain to begin different rituals in the community. Ritual specialists always start their incantations by calling upon Kanchenjunga in traditions such as Chyu Rum Faat, a ritual observed for the worship of the mountain. During this ritual, stones are erected in twos and threes, with the largest stone representing Mt.

Kanchenjunga. The centrality of this mountain in the Rong worldview is apparent in the residential pattern of the community, as people ensure they can see the mountain from where they live. The snow melt that turns into rivers and streams reveals their dependence on the mountain for their sustenance and livelihood.14 Even at death, Kanchenjunga stands tall, since in Rong cosmology, when someone dies, the soul returns to their mountain of origin. Thus, the veneration of the guardian deity of Sikkim has deep roots in the Rong belief system.

In October 2023, Sikkim witnessed a devastating glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) along with incessant rain, floods, and landslides. This GLOF destroyed the biggest hydropower project in Sikkim, killing over forty people and ruining hundreds of homes and livelihoods downstream. Indeed, the mountains and rivers of this region have been heavily impacted by anthropogenic climate crises. Newspaper editorials and journalists started reaching out to Rong activists to hear their perspectives as their protests against dams from almost fifteen years ago were being recalled, and the Indigenous knowledge of climate change was being acknowledged. The Rongs respect and revere the environment they live in. They place value in kinship obligations—as we have seen with the eldest brother—and share a reciprocal relationship between humans and non-humans. If they fail to recognize this relationship, they believe there may be consequences.

Few Rong scholars have advocated a thorough study of Rong folk tales to understand their religious beliefs. Many of these tales revolve around nature and various interactions with supernatural beings. In this light, I return to the creation story in which the eldest brother Kongchen Konghlo was created. At that time, matli pano or the earthquake king was also created. But the world was filled with water, so Itbudebu Rum created soil/earth on matli pano’s body so different beings could inhabit the Earth. But the earthquake king was not happy and would often shake causing floods and earthquakes. In order to control the earthquake king, Kongchen Konghlo was placed on his chest so the eldest brother could control and protect everyone from the rage of the earthquake. This story underscores the importance of relational bonds and the role of the eldest brother in protecting the environment of Sikkim Himalaya. While Mt. Kanchenjunga serves as a protector deity15 today, the Indigenous Rong belief system has long been aware of the “relationship of material, semiotic and spiritual life,”16 as seen by the eldest brother protecting both the human and nonhuman beings of the land.

1 Gorer was one of the first anthropologists to study the Rong people in the 1930s. He found their religion to be complicated as they practised simultaneously two “contradictory” religions. See Geoffrey Gorer, The Lepchas of Sikkim (Delhi: Cultural Publishing House, 1984), 181.

2 Davide Torri, “In the Shadow of the Devil” in Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia (London: Routledge, 2010), 148.

3 Herbert Hope Risley, The Gazetteer of Sikkim (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1894).

4 John Morris, Living with the Lepchas (London: William Heinemann, 1938), 287.

5 David McDonald, Touring in Sikkim and Tibet (Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1930), 8.

6 Robin Wright, “Indigenous Religious Traditions,” in Lawrence Sullivan, ed., Religions of the World (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012), 31-50.

7 Charisma K. Lepcha, “The Scottish Mission in Kalimpong,” in Markus Viehbeck, ed., Transcultural Encounters in the Himalayan Borderlands (Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing, 2017), 73.

8 In 2006, as part of the government of India’s Mega Power policy, hydropower projects opened up to the private sector, reaching Sikkim along with the rest of Northeast India.

9 Beginning in 1642, Sikkim was ruled by the Namgyal dynasty before it became part of India in 1975.

10 Deborah Bird Rose, Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal View of Landscape and Wilderness (Canberra, Australian Heritage Commission, 1996), 8.

11 Ibid, 7.

12 John A. Grim, “Recovering Religious Ecology with Indigenous Traditions” in Indigenous Traditions and Ecology, ed. John A. Grim (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998).

13 Mircea Eliade, “Archaic Myths and Historical Man,” (typescript and offprint, undated), 6070.

14 Charisma K. Lepcha, “Lepcha water view and climate change in Sikkim Himalaya” in The New Himalayas: Symbiotic Indigeneity, Commoning Sustainability, ed. Dan Smyer Yü and Erik de Maaker (London: Routledge, 2021), 43.

15 Kalzang Dorjee Bhutia, “Living with the Mountain: Mountain Propitiation Rituals in the Making of Human-Environmental Ethics in Sikkim,” Journal of Buddhist Ethics (2021): 261-294.

16 John A. Grim, “Indigenous Lifeways and Ecology,” 2019.

Bibliography

Bhutia, Kalzang Dorjee. “Living with the Mountain: Mountain Propitiation Rituals in the Making of Human-Environmental Ethics in Sikkim.” Journal of Buddhist Ethics (2021): 261-294.

Eliade, Mircea. “Archaic Myths and Historical Man.” Typescript and offprint, undated.

Gorer, Geoffrey. The Lepchas of Sikkim. Delhi: Cultural Publishing House, 1984 (reprint).

Grim, John A. “Recovering Religious Ecology with Indigenous Traditions” in Indigenous Traditions and Ecology, ed. John A. Grim. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Grim, John A. “Indigenous Lifeways and Ecology.” Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, 2019. https://fore.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/JG%20Indigenous%20Lifeways%20and%20Ecolog y%20.pdf.

Lepcha, Charisma K. “The Scottish Mission in Kalimpong and the Changing Dynamics of Lepcha Society” in Transcultural Encounters in the Himalayan Borderlands: Kalimpong as a “Contact Zone,” ed. Markus Viehbeck. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Press, 2012.

Lepcha, Charisma K. “Lepcha water view and climate change in Sikkim Himalaya” in The New Himalayas: Symbiotic Indigeneity, Commoning Sustainability, ed. Dan Smyer Yü and Erik de Maaker. London: Routledge, 2021.

Morris, John. Living with the Lepchas. A Book about Sikkim Himalayas. London: William Heinemann, 1938.

Rose, Deborah Bird. Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal View of Landscape and Wilderness. Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

Risley, Herbert Hope. The Gazetteer of Sikkim. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1894.

Torri, Davide. “In the Shadow of the Devil: Traditional patterns of Lepcha Culture Reinterpreted” in Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia: Disease, Possession and Healing., ed. Fabrizio Ferrari. London: Routledge, 2010.